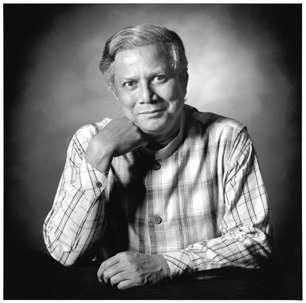

Muhammad Yunus Reflects on Working Toward Peace

My

efforts to empower Third World poor began, appropriately

enough, with an independence movement-the independence of

Bangladesh. In 1971, my homeland was confronted with a war,

bloodshed, and a tremendous amount of misery. During that

war, I was teaching in the United States. But after nine

months of fighting, Bangladesh became independent and I

went back, thinking I would join the people in the rebuilding

process and help create the nation of our dreams. As the

days went by, however, the situation in Bangladesh did not

improve. It started sliding down fast, and we ended up with

a famine at the end of 1974.

My

efforts to empower Third World poor began, appropriately

enough, with an independence movement-the independence of

Bangladesh. In 1971, my homeland was confronted with a war,

bloodshed, and a tremendous amount of misery. During that

war, I was teaching in the United States. But after nine

months of fighting, Bangladesh became independent and I

went back, thinking I would join the people in the rebuilding

process and help create the nation of our dreams. As the

days went by, however, the situation in Bangladesh did not

improve. It started sliding down fast, and we ended up with

a famine at the end of 1974.

By this time, I was teaching at Chittagong University

on the outskirts of Chittagong City, Bangladesh, and I felt

terrible. There, I taught economics in the classroom with

all the enthusiasm of a brand-new Ph.D. from the United

States. I felt as if I knew everything, that I had all the

solutions. But then I would walk out of the classroom and

see skeletons all around me, people waiting to die. There

are many, many ways to die, but none is so cruel as to die

of hunger; death inches toward you, you see it, and you

feel helpless because you can't find one handful of food

to put inside your mouth. And the world moves on.

I couldn't cope with this daily tragedy. It made me realize

that, whatever I had learned, whatever I was teaching, was

all make-believe; it had no meaning for people's lives.

So I started trying to find out why the people in the village

next door to the university were dying of hunger. Was there

anything I could do as a human being to delay the process,

to stop it, even for one person?

I traveled around the village and talked with its people.

Soon, all my academic arrogance disappeared. I realized

that, as an academic, I wasn't really solving global problems;

I wasn't even solving national problems. I decided to abandon

my bird's-eye view of the world, which allowed me to look

at problems from above, from my ivory tower in the sky.

I assumed, instead, the worm's-eye view and tried to probe

whatever came right in front of me-smelling it, touching

it, seeing if I could do something to improve it. Trying

to involve myself in whatever capacity I could, I learned

many things in my travels.

But it was one particular incident that pointed me in

the right direction. I met a woman who was making bamboo

stools. After a long discussion, I discovered that her profit

for the stools averaged the equivalent of two American pennies

a day. I could not believe anyone could work so hard, create

such beautiful bamboo stools, and make so little. She explained

that she didn't have the money to buy the bamboo that goes

into the stools; she had to borrow from the trader, who

required that she sell the product to him alone and at a

price he decides. She was virtually bonded labor to that

person. And how much did the bamboo cost? She said about

twenty cents; if it was good bamboo, twenty-five cents.

I said, "My god, people suffer for twenty cents and

there's nothing anyone can do about it?"

Thinking it over, I wondered whether I should just give

her the twenty cents. But then I came up with a better idea:

I could make a list of people in the village who needed

that kind of money to be self-employed. After several more

days of traveling, a student of mine and I came up with

a list of forty-two such people. When I added up the total

dollars they needed, I experienced the biggest shock of

my life: it added up to twenty-seven dollars! I felt ashamed

to be a member of a society that could not provide twenty-seven

dollars to forty-two hard-working, skilled human beings.

To escape my shame, I took the twenty-seven dollars out

of my pocket and gave it to my student and said, "Take

this money. Give it to those forty-two people we met and

tell them this is a loan, which they can pay back whenever

they are ready. In the meantime, they can sell their product

wherever they get a good price."

The people of the village were quite excited to receive

the money; such a thing had never happened to them before.

Seeing such excitement made me wonder what more I could

do to help them. Should I continue providing them money

or should I arrange for them to secure their own funds?

I thought of the bank located on campus. In a meeting with

the manager, I suggested that his bank lend the money to

the forty-two people I had met.

"You're crazy!" he said. "It's impossible!

How can you lend money to the poor people? They're not credit

worthy." . . . The bankers had been trained to believe

that poor people are not capable of running profitable businesses.

Their minds were blind to the results they had been shown.

Luckily, my mind had not been trained that way.

Finally I thought, why am I trying to convince them? I'm

already convinced that poor people can be advanced business

loans and will pay them back. So why don't I just set up

a separate bank of my own?

I wrote up a proposal and went to the government for permission.

It took two years of convincing. . . . At last, in 1983,

Grameen Bank-a formal, independent financial institution-was

opened. I founded it as an alternative to the current banking

system, which I found to be biased against both the poor

and women. . . .

Recognizing this bias, I wanted to make sure that women

made up half of all Grameen's borrowers. But it wasn't easy

to persuade the women in Bangladesh to join the bank. A

man isn't even allowed to address a woman in her village.

The usual response I heard was, "No, I don't need

money. Give it to my husband." We kept telling them

that we understood their husband could take it but that

we wanted to give the money to the women if they needed

it for a business idea. Yet, they would say, "No, I

don't have an idea." And that was repeated in village

after village, by woman after woman. It took a lot of convincing

before any woman could believe that she, herself, could

use a loan to earn income. All we needed was patience. We

asked that women borrow from Grameen in groups of five and,

once we were able to convince one woman, our work was half

done. She then was an example that convinced her friends

and then her friends' families and so on. . . .

Many women couldn't believe someone trusted them enough

to loan them such an amount of money. As tears rolled down

their cheeks, they promised to work very hard and make sure

they paid back every penny of it. And they did. Grameen

requires tiny weekly payments so that, over the course of

one year, business loans can be paid back with interest.

By the time the loans are paid off, the women are completely

different people. They have explored themselves, found themselves.

Others may have told them they were no good, but on the

day a loan is paid off, the women feel as though they can

take care of themselves and their families.

We noticed so many good things happening in the families

where the woman was the borrower instead of the man. So

we focused more and more on the women, not just 50 percent.

Today, Grameen Bank works in thirty-six thousand villages

in Bangladesh; has 2.1 million borrowers, 94 percent of

them women; and employs twelve thousand people. The bank

completed its first billion dollars in loans four years

ago, and we celebrated it. A bank that starts its journey

giving twenty-seven dollars in loans to forty-two people

and comes all the way to a billion dollars in loans is cause

for celebration. We felt good to have proven all those banking

officials wrong. . . .

I went back to the officials who are now my banking colleagues

and admonished them: "You said poor people are not

loan worthy. But for twenty years, they've been showing

every day who is worthy and who isn't. It's been the rich

people in Bangladesh who haven't paid back their loans because

it's been only the rich people who were granted them. With

Grameen Bank, it's the poor people who are paying back."

Our recovery rate has remained more than 98 percent since

we began. So my question now is, are the bank's people worthy?

Researchers say that there must be some trick to it-I

can't be reporting the right figures, I'm hiding things.

But when they investigate our records, they see the same

numbers. They come in with hostility and leave as great

admirers of our bank. Researchers now say that the income

of all our borrowers is steadily increasing. The World Bank

reports that one-third of our borrowers have clearly risen

above the poverty line, another one-third are a matter of

months or a couple of years away from this achievement,

and the remaining one-third are at different levels below

that. I say, if you can run a bank, lend money, get your

money back, cover all your costs, make a profit, and get

people out of poverty-what else do you want?

Are poor people loan worthy? Does the world still wait

for evidence? Does it care? I keep saying that poverty is

not created by poor people; poverty is created by the institutions

we have built around us. We must go back to the drawing

board to redesign those institutions so they do not discriminate

against the poor as they do now. We have heard about apartheid

and felt terrible about it, but we don't seem to feel anything

about the apartheid practiced by financial institutions.

Why should some potential entrepreneurs be rejected by a

bank simply because they are thought to be unworthy of a

loan? By the evidence, it is clear that the opposite is

true.

It is the responsibility of all societies to ensure human

dignity for every member of that society, but we haven't

done very well in that endeavor. We talk about human rights,

but we don't link human rights with poverty. Poverty is

the denial of human rights. And it's not just the denial

of one human right-put together all the many ways our society

denies human rights and that spells poverty.

Grameen-type programs are now popping up in many countries.

To my knowledge, fifty-six countries-including the United

States-are involved in such endeavors. But the effort doesn't

have the momentum it needs. There are 1.3 billion people

on this planet who earn the equivalent of one American dollar

or less a day, who suffer extreme poverty. If we create

institutions capable of providing business loans to the

poor for self-employment, they will see the same success

we have seen in Bangladesh through Grameen Bank. I see no

reason why anyone in the world should be poor.

Biography

Resources for Teachers

and Students