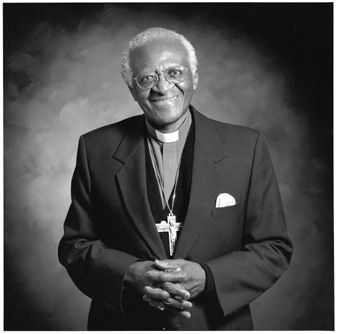

Archbishop Desmond Tutu Reflects on Working Toward Peace

When

I was a boy in South Africa, thousands of blacks were arrested

daily under the iniquitous pass-law system, which severely

curtailed our freedom of movement. As a black person over

the age of sixteen you had to carry a pass. It was an offense

not to have it on your person when a police officer accosted

you and demanded to see it. I remember vividly, when I would

accompany my schoolteacher father to town, how sorry I felt

for him when he was almost invariably stopped. Now there

was something funny for you: Because my father was an educated

man, he qualified for what was called an exemption. Ordinary

pass laws did not apply to him in that he had the privilege

denied to other blacks of being able to purchase the white

man's liquor without running the risk of being arrested.

But for the police to know he was exempted, he had to carry

his superior document. His exemption, therefore, did not

spare him the humiliation of being stopped and asked peremptorily

and rudely to produce it in the street. This kind of treatment

gnawed away at your very vitals.

When

I was a boy in South Africa, thousands of blacks were arrested

daily under the iniquitous pass-law system, which severely

curtailed our freedom of movement. As a black person over

the age of sixteen you had to carry a pass. It was an offense

not to have it on your person when a police officer accosted

you and demanded to see it. I remember vividly, when I would

accompany my schoolteacher father to town, how sorry I felt

for him when he was almost invariably stopped. Now there

was something funny for you: Because my father was an educated

man, he qualified for what was called an exemption. Ordinary

pass laws did not apply to him in that he had the privilege

denied to other blacks of being able to purchase the white

man's liquor without running the risk of being arrested.

But for the police to know he was exempted, he had to carry

his superior document. His exemption, therefore, did not

spare him the humiliation of being stopped and asked peremptorily

and rudely to produce it in the street. This kind of treatment

gnawed away at your very vitals.

Years later, after I was grown and married, and my wife,

Leah, and our children returned from England, where I had

gone to study theology, I faced an exquisite irony. My family

was having a picnic on the beach. The portion of the beach

reserved for blacks was the least attractive, with rocks

lying around. Not far away was a playground, and our youngest,

who was born in England, said, "Daddy, I want to go

on the swings," and I said with a hollow voice and

a dead weight in the pit of my stomach, "No, darling,

you can't go." What do you say, how do you feel, when

your baby says, "But Daddy, there are other children

playing there?" How do you tell your little darling

that she cannot go because though she is a child, she is

not that kind of child. And you died many times and were

not able to look your child in the eyes because you felt

so dehumanized, so humiliated, so diminished. I probably

felt as my father felt when he was diminished in the eyes

of his young son.

When I became archbishop of Cape Town in 1986, I set myself

three goals. Two had to do with the inner workings of the

Anglican Church. The third was the liberation of all our

people, black and white. That was achieved on April 27,

1994, when Nelson Mandela became South Africa's first democratically

elected president. The world probably came to a standstill

on May 10, the day of his inauguration. If it did not stand

still then, it ought to have, because nearly all the world's

heads of state and other leaders were milling around in

Pretoria.

A poignant moment that day came when Mandela arrived with

his elder daughter as his companion, and the various heads

of the security forces, the police, and the correctional

services strode to his car, saluted him, and then escorted

him as head of state. It was poignant because only a few

years earlier he had been their prisoner. What an extraordinary

turnaround! President Mandela invited his white jailer to

attend his inauguration as an honored guest, the first of

many gestures he would make in his spectacular way, showing

his breathtaking magnanimity and willingness to forgive.

This man, who had been vilified and hunted down as a dangerous

fugitive and incarcerated for nearly three decades, would

soon be transformed into the embodiment of forgiveness.

He would be a potent agent for the reconciliation he would

urge his compatriots to work for, and which would form part

of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission he would appoint

to deal with our country's past.

Since that day, our nation has sought in various ways

to rehabilitate and affirm the dignity and personhood of

those who for so long have been silenced, have been turned

into anonymous, marginalized ones. I have been privileged

to be involved in the rehabilitation effort through the

Truth and Reconciliation Commission, to which the president

appointed me and sixteen others in September 1995. It was

the commission's goal to reach out to as many South Africans

as possible, offering amnesty to all, both those who had

been victims and those who had been perpetrators during

apartheid's long reign. Our slogan was: The truth hurts,

but silence kills. Our aim was to engage all South Africans

in the work of the commission, ensuring that all would have

the chance to be part of any serious and viable proposal

for healing and reconciliation.

At first we feared that few would come forward, but we

need not have worried. We ended up obtaining more than twenty

thousand statements. People had been bottled up for so long

that when the chance came for them to tell their stories,

the floodgates opened. I never ceased to marvel, after these

people had told their nightmarish tales, that they looked

so ordinary. They laughed, they conversed, they went about

their daily lives looking to all the world to be normal,

whole persons with not a single concern in the world. And

then you heard their stories and wondered how they had survived

for so long carrying such a heavy burden of grief and anguish

so quietly, so unobtrusively, with dignity and simplicity.

How much we owe them can never be computed.

The hearings were particularly rough on the interpreters,

because they had to speak in the first person, at one time

telling a victim's story and at another telling a perpetrator's.

"They undressed me. They opened a drawer and then they

stuffed my breast in the drawer, which they slammed repeatedly

on my nipple until a white stuff oozed. We abducted him

and gave him drugged coffee and then I shot him in the head.

We then burned his body . . ." It could be rough as

they switched identities in this fashion. Even those physically

distant from the testimony were deeply affected. The head

of our transcription service told me that one day, as she

was typing the manuscripts of the hearings, she did not

know she was crying until she saw the tears on her arms.

In January 1997, while still sitting on the commission,

I learned that I had prostate cancer. It probably would

have happened whatever I had been doing. But it seemed to

demonstrate that we were engaging in something costly. Forgiveness

and reconciliation were not to be entered into lightly,

facilely. My illness seemed to dramatize the fact that it

is a costly business to try to heal a wounded and traumatized

people and that those engaging in this crucial task may

bear the brunt themselves. It may be that we have been a

great deal more like vacuum cleaners than dishwashers, taking

into ourselves far more than we knew of the pain and devastation

of those whose stories we had heard.

But suffering from a life-threatening disease also helped

me have a different attitude and perspective. It has given

a new intensity to life, for I realize how much I used to

take for granted-the love and devotion of my wife, the laughter

and playfulness of my grandchildren, the glory of a splendid

sunset, the dedication of my colleagues. The disease has

helped me acknowledge my own mortality, with deep thanksgiving

for the extraordinary things that have happened in my life,

not least in recent times. What a spectacular vindication

it has been, in the struggle against apartheid, to live

to see freedom come, to have been involved in finding the

truth and reconciling the differences of those who are the

future of our nation.

Biography

Resources for Teachers

and Students