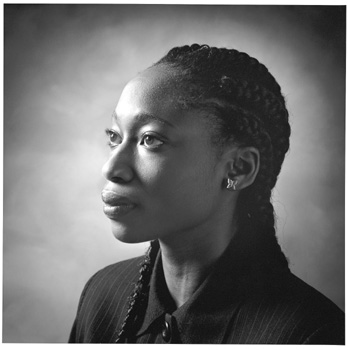

Hafsat Abiola Reflects on Working Toward Peace

My

country, Nigeria, is home to 120 million people-one fifth

of continental Africa's population-who come from more than

two hundred ethnic groups. Each group has its unique way

of being, of relating to others, and of contributing. My

group is the Yoruba. We are generally found in western Nigeria

and are famous for our arts, clothing, and music. I love

being Yoruba, Nigerian, and African because I come from

a rich heritage and yet, because so much needs doing in

my home, I know I will be kept busy.

My

country, Nigeria, is home to 120 million people-one fifth

of continental Africa's population-who come from more than

two hundred ethnic groups. Each group has its unique way

of being, of relating to others, and of contributing. My

group is the Yoruba. We are generally found in western Nigeria

and are famous for our arts, clothing, and music. I love

being Yoruba, Nigerian, and African because I come from

a rich heritage and yet, because so much needs doing in

my home, I know I will be kept busy.

Of all the things that serve my growth, I love best the

stories and myths told to me by my parents and the Nigerian

people I meet. My thoughts on peace begin with a story my

dad told when he was campaigning in Nigeria's 1993 presidential

election:

Sometimes a village is beset with problems-disease, famine,

conflict, and floods. All these problems come at once and

despite all the best efforts of members of the community,

the problems are immune to solutions. In such a situation,

the village believes they may have done something to upset

the gods, so they will gather all their best possessions

together to offer as gifts to the gods. They then ask one

of their best sons to present the gifts on their behalf.

When the gods are presented with the gifts, they may become

pacified and allow peace and prosperity to reign in the

land. But sometimes, they are so angry they will take the

best son, as well as the gifts, after which they are pacified

and allow peace and prosperity to reign. From this story,

I took the lesson that peace comes from contributing the

best we have, and, often, all that we are, toward creating

a world that supports everyone.

In much of precolonial Nigeria, and indeed Africa, ethnic

nations organized people within communities into peer groups

and trained them, from babyhood to old age, to serve their

communities. When successful, this system provided all members

of a community not only with a sense of belonging but also

with a vehicle for helping to shape the community's direction

and pace of change. In this system, people knew they were

entitled to help resolve any issue that affected the community.

This sense of entitlement grows out of a series of rituals

that begin the day a child is born. When a baby is born,

after the first few seconds, it lets out a yelp, which announces

its arrival, and which is met by expressions of joy. Among

the Yoruba, the arrival is acknowledged with a naming ceremony

where parents give names that express rich meaning and hopes

for the baby. When I arrived, my parents named me Hafsat

Olaronke, which means the treasured one and honor is being

cared for. For my parents, they saw in me one who would

be cherished and who would bring honor to her community.

Many in other parts of the world are impressed when they

discover my name's meanings, but the truth is that most

African names have beautiful meanings.

Mark Nepo, an American poet, narrates the story of the

Khoisan, a nomadic people found in southern Africa. According

to Nepo, when a Khoisan returns from a journey and meets

another from his community, he raises his hand and says,

"I am here," and the other replies, "I see

you." These practices are more than simple greetings;

they affirm our belonging to the community and our right

to contribute.

Nigeria is a place beset with problems, and all its members

are needed if we are to meet the challenges we face. Unfortunately,

until very recently, my country was controlled by a series

of military governments who denied most Nigerians the right

to make their contributions. Even in the period since the

military relinquished power to a democratically elected

government, many exclusionary attitudes-from class to ethnic

and religious divisions-as well as a general lack of trust

or sense of community, have effectively denied most people

the freedom to engage with their country's challenges.

And yet, despite the obstacles, both individuals and groups

are constantly announcing their presence, or asking the

questions, Do I belong? Can I contribute? Am I accepted?

Their queries are rarely met by affirmative or empowering

replies. Instead they hear jeers, or expressions of disinterest,

or obnoxious interrogations: "Who asks? What community?

What have you ever done anyway?" Nothing about this

process is enlightening, just humiliating.

This is because, unlike the small community, where every

person lives in the illusion of having the same ideals,

beliefs, and values as everyone else, in the larger context

of plural communities-be it in country, continent, or globe-we

live in the illusion of absolute difference. So, fearing

the possibility that the interaction will change us, we

magnify the threat involved in engaging with that which

differs from us. Change is stressful, and costly, because

it requires learning to navigate the unfamiliar. In the

end, you cannot work with anyone who is different, and problems

that could be resolved if we allowed everyone to contribute

the best of themselves begin to look intractable.

The Persian poet Jalaludin Rumi wrote: "Out beyond

ideas of right and wrong doing there is a field. I will

meet you there." If there is to be space for us to

speak into, we need to learn also to listen. We are the

creators of this space. We must each take responsibility

for examining our values, ideals, and beliefs and for learning

to understand those held by others, enough so that we can

help them and ourselves consider new possibilities.

In the end of my dad's story, he said that poverty, violent

conflict, malnutrition, and disease were all increasing

across Nigeria. And he asked to be able to bear our country's

gifts, in order to secure for us peace and prosperity. He

won the election but served out his term in solitary confinement,

incarcerated by the military, and died on the eve of his

release in 1998. But here was the difference he made: across

ethnic, religious, and class divides, the people said yes!

This search for validation is universal. It is beautiful

when these inquiries meet with affirmation, because it allows

a person to stride forward with all he has to give. There

is a story told by the conductor of the Boston Philharmonic

Orchestra, Ben Zander: a maestro conductor, after having

conducted a brilliant symphony, races out of the concert

hall and into a waiting car, imperiously commanding the

driver, "Drive!" When the driver asks, "Where

to?" the conductor boldly responds, "Anywhere!

The world needs me!"

Peace comes from being able to contribute the best that

we have, and all that we are, toward creating a world that

supports everyone. But it is also securing the space for

others to contribute the best that they have and all that

they are. In case you are still wondering-no, it was not

a wrong turn that brought you here. You do belong here and

there is a contribution uniquely yours that is needed. Welcome

and good luck.

Biography

Resources for Teachers and Students